By Jerry Duggan

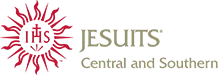

In the necrology of the Jesuits USA Central and Southern Province, one date stands out: September 10. On that day in 1931, eleven Jesuits died during a not-to-be-forgotten hurricane in what is now Belize.

Founded in 1887 in what was then British Honduras (present-day Belize) as a boarding college, St. John’s College (then known as the Select School) enjoyed substantial growth over its first few decades.

Soon, increased enrollment pushed the institution beyond the limitations of its original facility. In 1916, a cornerstone for a new campus was laid at Loyola Park, a swamp land one mile south of Belize City. While this location was picturesque, it was surrounded by water, making it especially susceptible to hurricane damage.

Still, the new campus was built, and the College continued to grow in both enrollment and prestige. In 1931, the school survived a yellow fever outbreak. The outlook was optimistic, but everything changed in just a few hours.

In the waning days of August 1931, a weather disturbance developed off the coast of Africa. It crossed the Atlantic but did not gain significant strength until it entered the Caribbean Sea on September 6.

A Jesuit who served at the College, Fr. Bernard New, is said to have sketched the storm’s path on a blackboard. According to his sketch, the storm would not directly impact the area. In light of that prediction, the College planned to partake in festivities on September 10.

September 10 was an important civic holiday in British Honduras. On September 10, 1798, a group of British settlers known as Baymen fought off Spanish forces once and for all, after years of struggle between the two. After this defeat in the Battle of St. George’s Caye, the Spanish never returned to the area.

The day always brought with it a carnival-like atmosphere, akin to July 4 in the U.S. There were parades in the streets and gatherings of friends and family. A celebratory disposition pervaded the nation.

Such was the case in the morning hours of September 10, 1931 — the 133rd anniversary of the Battle of St. George’s Caye. Morning clouds and wind were slightly concerning, but par for the course, according to written accounts of the day.

At around 10 a.m., a heavy rain started, but then stopped. Any mild concern that had developed dissipated. The boarders at St. John’s had an early lunch at 11:00, in order to gather for a large parade in the early afternoon.

However, the weather worsened, and all afternoon celebrations were cancelled. By then it was too late to turn around for thousands of people who had traveled great distances to the city to celebrate.

The storm arrived quite suddenly in the early afternoon, and the College had no evacuation or shelter plan to speak of. The entire campus was destroyed, such that one survivor recounts there was “not a stick left standing.”

According to eyewitness accounts, cathedral steeples came tumbling down, winds of over 100 miles per hour relegated men to their hands and knees and 15-foot waves quickly wreaked havoc on the area.

The boys of St. John’s were in various places around campus at the time of impact, but it did not make any difference where they were, they all were holding on for dear life.

According to one account from a survivor, “the wind shrieked so loud that talking was out of the question. For about an hour and a half we lay flat, shivering and praying.”

After the first wave of the storm, there was a period of total calm, likely the eye of the storm passing directly over the campus. After that, the back bands made a direct hit and inflicted even more damage.

One survivor characterized this second impact as full of “pitiless rain, a wind with brush and mud, falling trees and an awful darkness.”

As conditions worsened, campus buildings crumbled one after another. First, the roof came off the gymnasium, then academic buildings. Trees collapsed on those that remained intact. Piles of wreckage formed, with bodies underneath. After hours of terror, the storm passed, but left behind incalculable loss.

Approximately 2,500 people were killed in the storm altogether, including 33 at St. John’s. Of those 33, 11 were Jesuits — 6 priests, 4 scholastics and 1 brother. The other 22 fatalities included 18 students and 4 servants.

Still, according to survivors, even the worst day in the College’s history was not void of God’s grace. The selflessness and surrender to God exhibited by the dying is proof that God was at work, even on days like September 10, 1931.

A Jesuit scholastic and survivor said of those who died: “All died peaceful deaths, not uttering a complaint. All were prepared to go as we said the Act of Contrition and spoke of the meeting with our dear Lord, who loves us and was soon to save us from our pains. There was no screaming as the water rose. Everyone was happy and resigned to death.”

After the storm ended, night fell, and survivors waded through floodwaters to search the wreckage for signs of life. One man managed to survive under a pile of rubble for 10 hours and was rescued at around 2 a.m., at which point he attended an impromptu Mass that was held in the school’s devastated chapel.

Over the following days and weeks, survivors surveyed the damage and tried to get back to normal. But, the legacy and heroism of those who lost their lives was not forgotten.

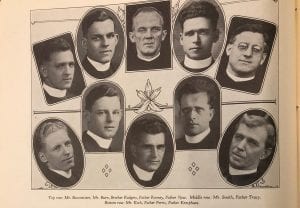

Here follows the Jesuits who died September 10, 1931, many of whom acted heroically even on death’s door.

- Father Francis Kemphues was a pastor who saw his church and school destroyed as children were gathered with him for the ill-fated festivities of that day. Even with a broken leg and fractured skull, he absolved the dying, thinking of others before himself as he faced his own impending death.

- Father Charles Palacio was principal of the College. He led by example as a Man for Others, dying in the process of aiding other injured Jesuits and students.

- Father Bernard New taught at the College. His sense of humor and skill for recruiting boys to the College on his mission trips made him a popular faculty member.

- Father Leo Rooney was a teacher and treasurer at the College. He had great zeal in his ministry, helped construct the College’s business school and was likely killed by a wave after he administered absolution to those around him.

- Father John Tracy was a gentle giant. He taught at the school and administered absolution to students before his death. He was found in a pile of wreckage, surrounded by his students who he cared for so deeply.

- Father William Ferris, a native of Ireland, was an older man who, having been healed of his ailments, served in Belize to give thanks to God for his health. He was killed by either the fall of a building or a tidal wave.

- Brother John Rodgers started out in the medical workforce, but ultimately determined a vocation to religious life was the right path for his life. He served as an infirmarian in Belize and was well-liked by students and brother Jesuits. He was trapped in a stairwell and killed when a campus building collapsed.

- Richard Koch was in his third year teaching at St. John’s. A quiet, small-statured man, Koch dedicated much of his time to the library and camera club. He always had a smile on his face, a smile that some say even death likely did not wipe away.

- Alfred Baumeister had been at St. John’s little more than a year and already had a tremendous impact on his class of 42 boys, with whom he was patient yet firm. He had tremendous passion for teaching and was killed by a falling building in the process of helping boys to safety.

- Deodato Burn attended St. John’s as a boy and had just returned to his alma mater to teach. His final act was leading a classroom of boys in an Act of Contrition.

- Richard Smith had just started at St. John’s a few months before the hurricane. He taught commercial subjects and math at the College and perished in a classroom.

Thank you to the Jesuit Archives and Research Center, who assisted with this story and provided images.